Building a Decentralized Identity Verification system on Solana (Part 1)

SMS is more than 35 years old and while it was mainly designed for communication, in practice we also use our mobile phone numbers as universal identifiers. We use them to login to apps like Uber and Venmo and for two-step verifications at banks and social media sites.

However, phone-numbers-as-identity has several big problems:

- SIM swap attacks are very real

- SMS messages are not encrypted

- It's expensive to get new phone numbers

- Verifications are relatively expensive: Twilio charges .75 pennies per message

- You don't really “own” your phone number, it belongs to the telco

- Phone numbers are not “friendly” identifiers

These problems boil down into several categories: security, ownership, and cost.

A different approach: Smart Contracts and Decentralized Identifiers

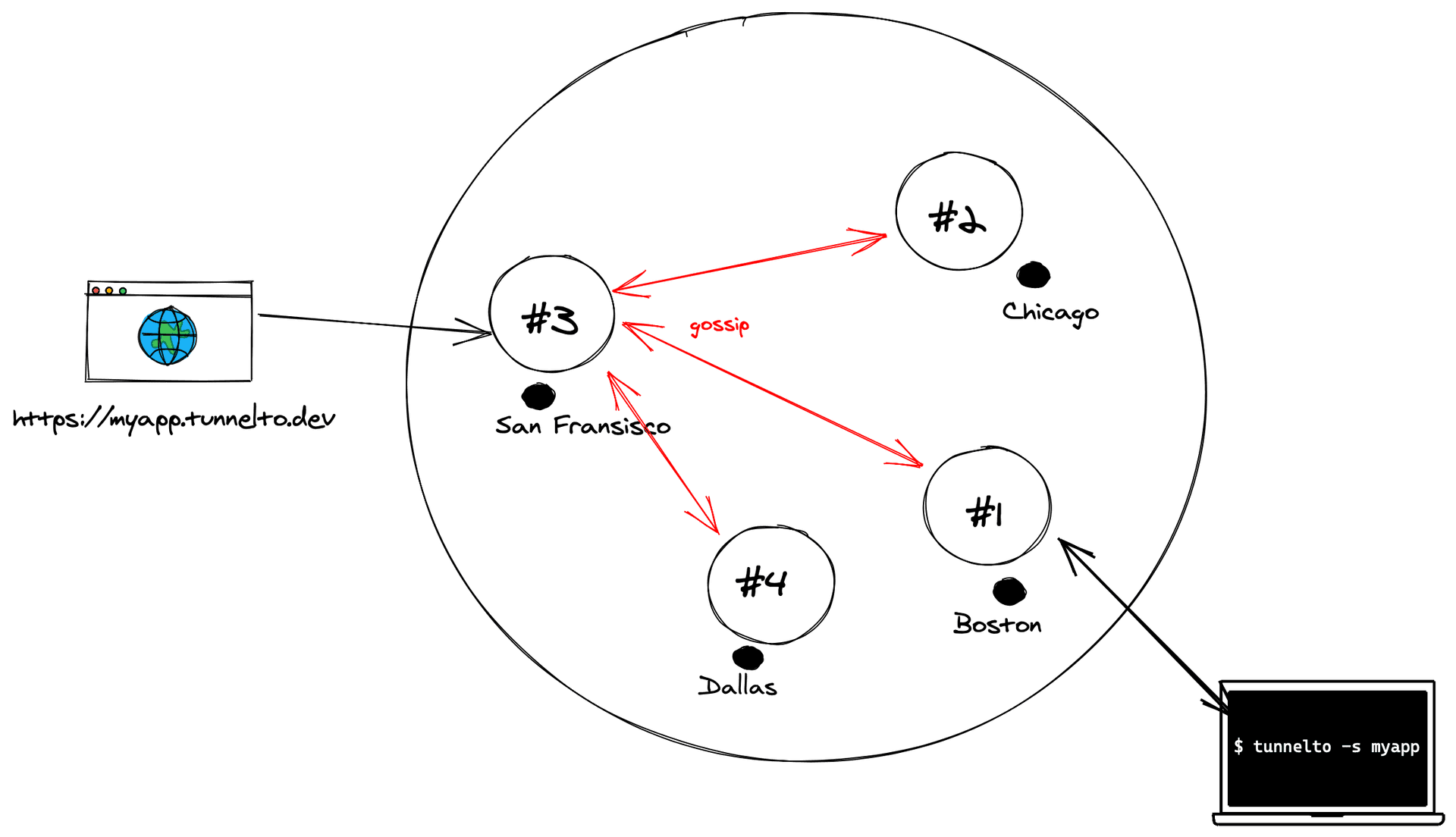

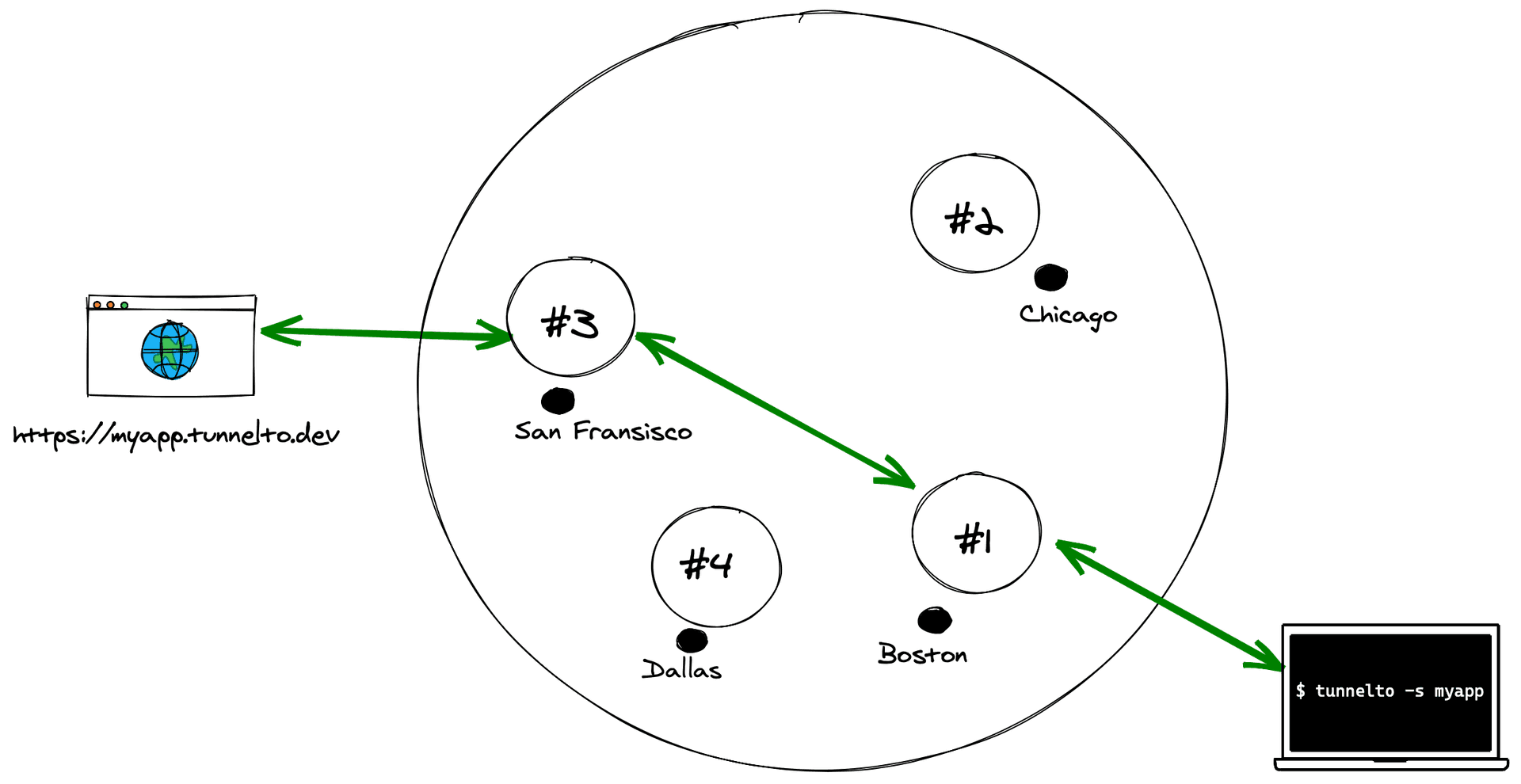

In this post series we'll present one way to build a new decentralized identity and verification system that improves on phone numbers. We're building it on the Solana blockchain solely with Smart Contracts (a.k.a Solana Programs).

Why a blockchain?

It's important to note that it is possible to build a similar system that is not on-chain — a centralized, trusted third-party service. We specifically stay away from this approach because we want the system to be provably correct and secure, and function transparently. Without a trusted third party, decentralized consensus is one approach to achieve this.

Why Solana?

- Transaction costs are negligible

- The account programming model is powerful

- Programs can be written in Rust (or any programming language that can target the LLVM BPF backend)

- The developer experience is first class (in part, thanks to frameworks like Anchor)

Overview

The idea is to replace phone numbers with friendly user identifiers, i.e. a username. Any person should be able to claim a username as their own (first come, first serve). Any service, i.e. AcmeInc, should be able to challenge any user to verify their identity. The verification flow needs to be as simple as it is for SMS:

- type in a username

- receive an auth challenge

- verify identity by responding to the challenge

To build this on chain, our smart contract needs to have several “instructions”:

- claimUsername

- challengeUser

- verifyChallenge

In this post series we'll cover some of the fundamentals of building in the Solana programming model and design, build and deploy a functioning program on chain that does decentralized identity verification as an attempt to offer an alternative to phone-number-as-identity.

We'll be writing our smart contract in Rust using the Anchor Framework. Anchor provides excellent interfaces for safety and dramatically cuts down on boilerplate code.

Solana's Programming Account Model

Accounts are how Solana programs store state on chain. Accounts are addressed by 256-bit numbers that may or may not be Ed25519 public keys. In addition to arbitrary amounts of data, Accounts also store several other important metadata attributes.

- Balance: the number of lamports in the account (1 Lamport = 0.000000001 SOL)

- Owner: an address of a program that owns this account, like the “SystemProgram”

- Executable: a boolean flag that indicates if the data in the account corresponds to a program or not

Accounts that are executable are programs. The address of a program account is often called the program id.

Transaction & Instructions

The programming model has several rules that are enforced. The most important rule for the context of this post is: “Only the owner may change account data.” This means that our smart contract is the arbiter of writing data to any account it owns.

A transaction contains one or more instructions to execute a program. Instructions specify the program to execute, data arguments for the program, and a list of accounts to read and potentially mutate. Transactions can optionally be signed by one or more private keys where the corresponding public keys must be the addresses of an account in the transaction.

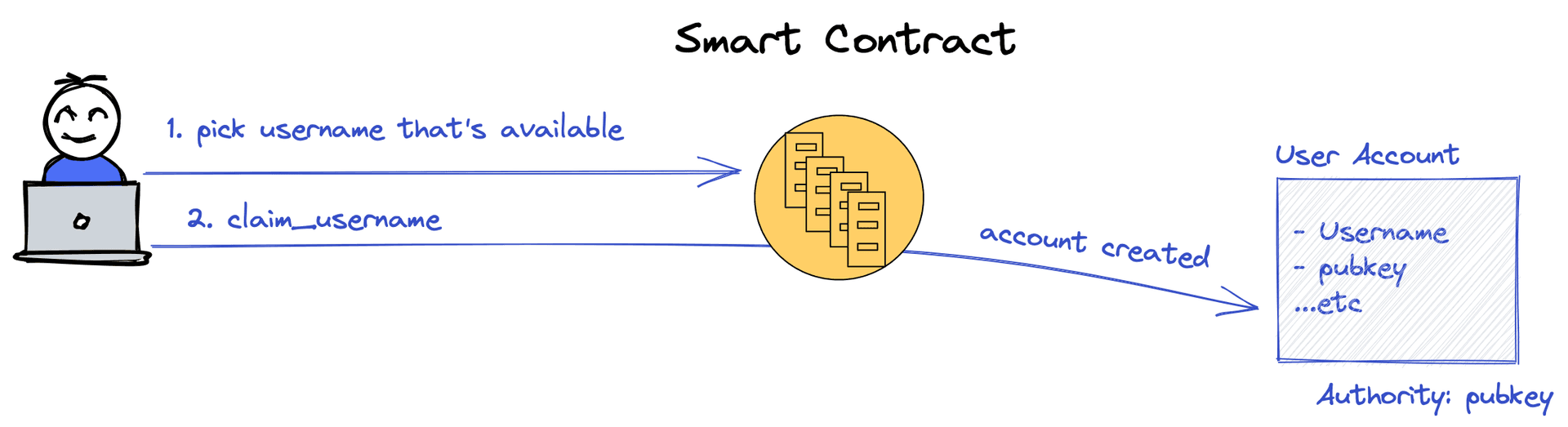

Claiming Usernames

The first instruction we need to support is claiming a username. To explain how we can do this on Solana we need to first explain what a Program Derived Address (PDA) is.

The User Address

When a username is claimed we want to create a unique Account whose owner is our smart contract program and the “authority” (or who the username is assigned to) is the public key of the first person to claim the username. We call this the User account. The User Account stores the binding between the username and the authority public key.

The core requirement this system must observe is that: usernames must be unique. Two user accounts with the same username cannot exist.

To accomplish this we can use a PDA. Namely, we derive a unique address for each username. The first user to submit a transaction that creates an account with this address is the authority for that username.

This address is not a real public key, it's just an address namespaced to our program address space. PDAs are useful for cross-program invocation because only the program can act as a signer on behalf of this account.

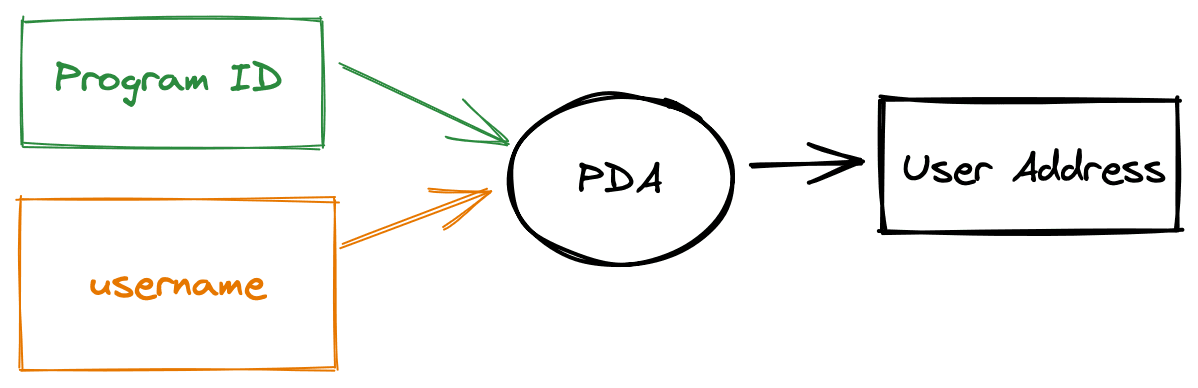

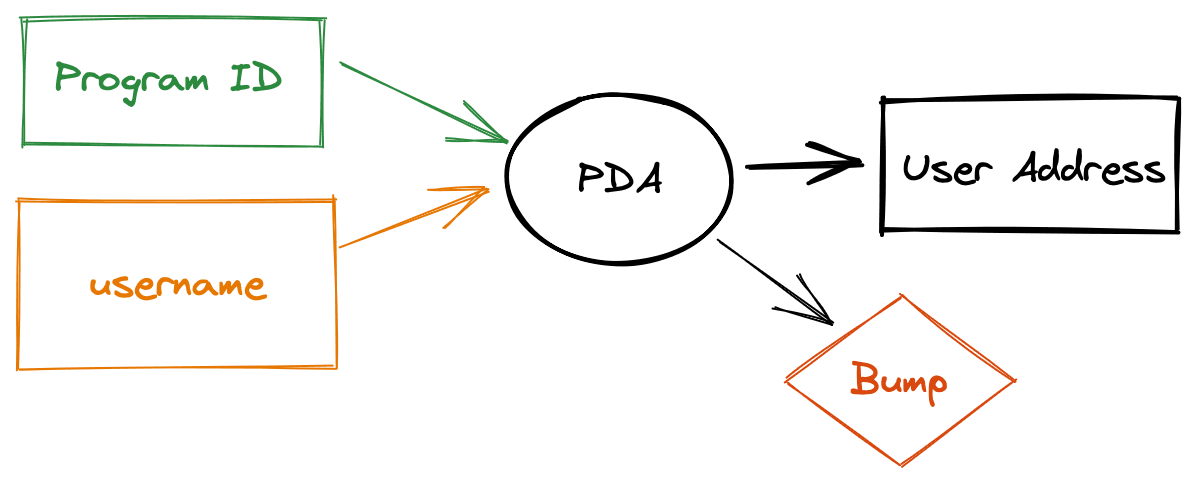

The PDA generation algorithm uses a cryptographic hash function to combine one or more “seeds” — in our case just the username — with the program id. Anybody can compute PDAs on behalf of any program.

The generation algorithm specifically creates an address off of the Ed25519 curve to ensure that a corresponding private key cannot exist. The PDA algorithm returns a 256-bit number that “bumps” the hash off of the curve.

The User Account

Abstracting the user account with a PDA is useful for us because it gives us a convenient way to ensure that only a single account exists per username. More conveniently, it gives us a trivial way to derive the user account address with only the username. Given somebody's username, I can compute their “user address” and therefore look up the user account on chain to get the user's real public key (the “authority”).

The important data we'd like to store is the authority as it binds the username to user owned public key. However, we also store the username and bump number. We do this for convenience, as we'll later see.

Claim Username Instruction

Now let's build the claim_username program instruction. The Anchor framework really starts to shine here as it abstracts away all the safety and account architecture into simple to use Rust procedural macros.

Note that most of the work is done by the time the code in the function gets executed. This is because Anchor's procedural macro is really generating lines of code to do account creation and initialization and all sorts of safety checks like account ownership and signature verification.

Up next

That's it for part 1! We've built the foundational smart contract to claim usernames and bind usernames to self-sovereign public keys. In part 2, we'll build “Service” accounts and show how they can be used to create an SMS-style challenge-response verification scheme on-chain using usernames instead of phone numbers.